Daniel H. Turtel considers himself to be a natural storyteller, “with the caveat that the ‘storytelling’ itself is probably the least intuitive part of telling a story for me,” he admits. “Dialogue, structure, word choice and cadence all come much more naturally to me, whereas with plot points I find that I really have to work to map them out.” The key ingredient to a compelling narrative lies in the pursuits of its actors. “An author needs to convey a clear sense of what their characters want. It doesn’t need to be much, it doesn’t need to be complex, and it doesn’t even need to be a relatable desire, but it needs to be salient. Motive and want lend credibility to the entire arc of the story – they create gaps between the worlds the characters inhabit and the worlds that the characters want to inhabit, and much of the action in fiction is how these gaps are ultimately spanned or not spanned.” Constructing a believable world often depends on a highly subjective tango between reader and author. Getting to know the characters is paramount. “The details that are important in making a world successfully immersive will vary writer to writer (and reader to reader). To me, the authenticity of a world is reliant on how much I believe in the characters, and that’s inevitably going to be based on the actions and interactions between them. I don’t have to like or understand the characters, but I do have to believe that they are doing things that they would really do. As simple as that sounds, it’s difficult to get right, and it speaks to the most difficult task in writing, which is to develop from nothing a fully-fledged psyche whose foundations, though fabricated, are credible and sufficiently explanatory. There’s nothing more jarring than to be reading something and have the thought: ‘I don’t think that character would really do that…’ And the best way to build up a credible, authentic psyche in the reader’s mind is to have a character interacting with its world — to see what they do when someone sits beside them on a park bench, or when a fly lands on their arm. If a character’s behavior in low-stakes, familiar situations can inform their behavior in high-stakes, plot-critical situations, and do so in such a way that is appreciable to the reader, then the writer has created an authentic character (despite its non-existence) and when a world is populated by enough of those, it’s going to feel immersive and real.”

Daniel asserts that telling Jewish stories telling Jewish stories is crucial in the face of rising antisemitism. “There are… many times in the past three-thousand years of Jewish history in which Jewish story-telling and relatability to the non-Jewish world would have probably gone a long way. But it’s just as important as ever because we seem to be at a juncture at which subtle and not-so-subtle antisemitism is making a strong run at being in vogue across a broad spectrum. The idea that a few celebrities would voice old and tired invective is less troubling to me than it is that coordinated groups on either side of the country would fly banners reiterating those claims. And while I don’t think that people who otherwise would not be predisposed to telling Jewish stories should jump on the bandwagon now, I do think that it’s critical that Jewish storytellers, wherever they are, refuse to be intimidated by such rhetoric or allow it to shape their work.” It’s not the responsibility of Jewish authors to limit themselves to only positive portrayals, because that simply is not reflective of humanity as a whole. “This is something I’ve had to think about a lot in regards to The Family Morfawitz, because the story is not a story about Jews being wonderful people; it’s a story in which a Jewish family stands in for Greco-Roman mythological figures, who tend to be pretty horrible, cruel and self-centered characters. I’ve already caught flak, and expect to catch some more, regarding the novel’s potential to perpetuate antisemitic stereotypes. But the reality is that Jewish people, just like every other people, can be good or bad, kind or cruel, and the majority of characters in this novel happen to be the bad and cruel kind. Nobody’s takeaway from Wuthering Heights is that all British people are horrible; similarly, it’s absurd to take a book about Jewish people sometimes being bad and extrapolate that all Jewish people are bad. It shouldn’t be the job of Jewish writers to dispel ancient antisemitic stereotypes, and it’s inappropriate to let modern (or eternal) prejudices affect one’s work.”

The aforementioned novel presents a family dynasty as compelling as it is unsavory. “The Family Morfawitz is a retelling of greco-roman myth as a multigenerational Jewish family saga. The idea for the novel came to me at my grandfather’s funeral in April of 2020, when it struck me that the first letters of his Hebrew name Zvi ben Chaim (Zvi, son of Chaim) could match up phonetically with Zeus, son of Cronus. In addition to being a perpetual mythology-geek, I was also reading Ovid’s Metamorphoses at the time (a local bookshop had drawn a sign suggesting that by adding a ‘C’ to ‘OVID’ one could update a timeless classic for the trials of modernity). I thought it would be fun to change ‘metamorphoses’ to ‘Morfawitz’ and change the story to be about a family of Jews instead of Olympians. Zeus became Zev, Hera became Hadassah, and clashes between titans and gods became the raging World Wars that shaped the twentieth century.” Historical strife mirrors the endless struggle for supremacy within the family. “The novel begins with the Morfawitz family being driven by pogroms from the Pale of Settlement, takes the family through Nazi Germany, and ends with their firm establishment in postwar New York City. Zev, like Zeus, is a pathological philanderer and adulterer. As Zev’s many illegitimate children begin to appear on the scene, each carves out his or her niche in the family company; some integrate well and rise, others have total meltdowns and run away, and others need to be excommunicated in order to preserve the family’s prestige. But behind every twist and turn lies Hadassah, who is the matriarch and the driving force behind the family’s success. The story uses Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a frame, but it does not presuppose any familiarity whatsoever with the text.” Hadassah is determined to overcome her past and move towards her perceived destiny of grandeur. Daniel states matter-of-factly that she is motivated by “family, status, family status and power. Her early life is defined by fleeing Nazi Germany, playing mother to her irresponsible siblings, and nurturing a gargantuan pride that is constantly at odds with her stark poverty. She wants and needs to control her world and her present, and it begins with controlling her past: she fabricates an illustrious Morfawitz family history and will stop at nothing to ensure an illustrious Morfawitz family future.”

Zev’s loyalty to Hadassah despite numerous affairs may be confusing for some, but it can be traced to mutual trauma from the past coupled with ruthless survivalism. “Just like Hadassah, Zev is also shaped by his brutal early childhood, which he first spent hiding in the Masovian forest, and then as a kapo at a concentration camp, where he was tasked with sorting his fellow Jews into those capable of work and those only fit for death. So it’s not so surprising that he is predisposed to assessing people in terms of what he can extract from them. What he can extract from Hadassah is: a channeling force for the raw but uncontrolled power he offers, some stability, and a partner who he can relate to. Theirs is more a union of utility and advantage than it is one of love, and yet – like all relationships – theirs evolves over time, and as they enter old age towards the end of the book, they are increasingly reliant on one another.” Meanwhile, their abandoned son Hezekial serves as a conflicted conduit for their story. “Hezekial gives us a unique perspective, because he’s been both in and out of the family. His mother, Hadassah, initially abandons him to an orphanage, but when she sees some use for him later on, she takes him back into her fold. Hezekial has spent his life balancing his desperate need to be accepted by a family that rejected him, and an equally strong desire to pay them back for their cruelty. This naturally gives his narration an unorthodox and tragicomic bent, the tone and inspiration for which comes from Yiddish literature and oral tradition.” For his part, Daniel continues to pour his heart into his craft. “I’m wrapping up a pretty advanced draft of my next novel now, but it’s still a little too early to talk about. I’ll say that theme is meant to be ‘who gets to write what and who gets to decide.’ It’s a fun book but a serious one and was totally exhausting to write, and I think I’d like to try something fun after, like a world-building series, but it’s too early to say!” He certainly knows how to leave us wanting more!

Read more about books on ClicheMag.com

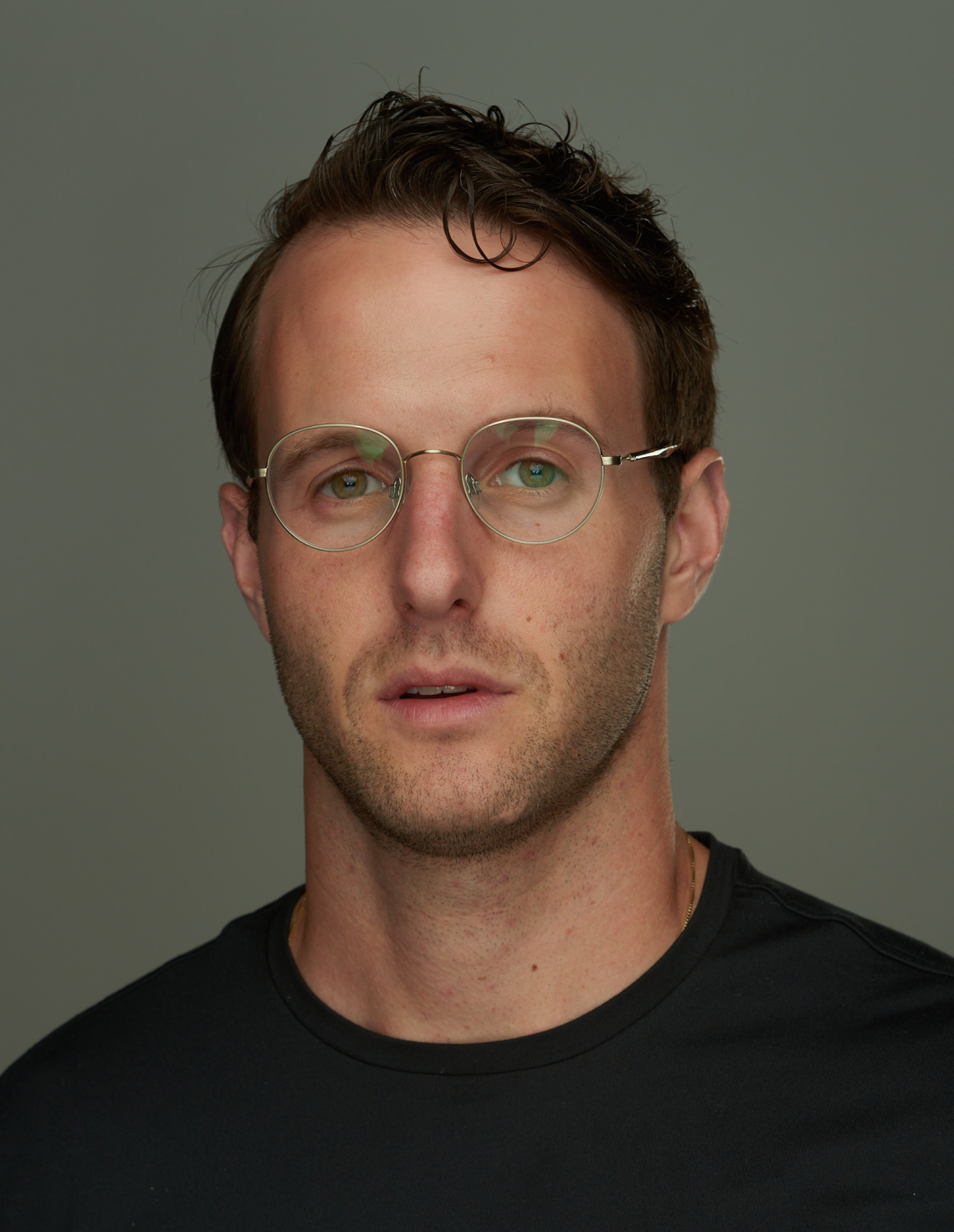

Author Daniel H. Turtel Depicts a Power Hungry Family’s Quest for Domination in “The Family Morfawitz.” Photo Credit: Courtesy of Daniel H. Turtel.